I spent the weekend after Donald Trump instituted his so-called Muslim ban glued to my mobile phone, trawling around the Internet for any scrap of news, and getting into arguments with strangers on social media.

It was probably not the most productive use of my time, but I found it did help me get out of my bubble a little. I don’t insult or make fun of people – instead, I ask them questions to draw out a bit more information about their point of view. I rarely receive a response, but I find that my attempts to communicate help me, in part, to figure out the principles behind their statements.

Their comments are often logically incoherent, but I think they are indicative of a particular world view. In one illustrative exchange, someone asked me why, as a British citizen, I was entitled to comment on events in the US. When I explained that I was both British and American, they replied that someone couldn’t be a patriotic citizen of two countries, because you can only pledge allegiance to one.

This reminded me of discussions I had with British citizens when I naturalised in the UK. They were somewhat taken aback that I was required to pledge allegiance to the Queen, as natural born citizens are not required to do so, except in certain, rather unusual cases (i.e. as a judge or an elected representative). This is also the case in the US – American children grow up pledging allegiance to the flag, but only naturalised citizens are required to pledge an oath of allegiance in an official ceremony. So one could argue that, if pledging allegiance is the sign of a true patriot, then only naturalised citizens are true patriots.

I didn’t get the opportunity to express this and further thoughts, such as the idea that believing someone can only pledge allegiance to one country sounds an awful lot like the sentiment that a person can only have one master. I don’t consider my country as my master, rather the reverse. As a free citizen in a democracy, I consider myself and my fellow citizens to be the masters, and our country to be our servant. Or perhaps the country is the parent and we, the citizens, are autonomous adult children. At any rate, I prefer to focus on the agency of citizens. But research has shown that Trump supporters have a more authoritarian bent, so they probably disagree.

Interestingly enough, the suspicion of immigrants can go the other way. When a friend of mine shared a statement from Mo Farrah on her Facebook feed, she received a curious comment from one of her British acquaintances. Essentially, this person argued that while he appreciated Farrah’s sentiment about Britain welcoming him as a citizen, he questioned the patriotism of any British citizen who wanted to leave his country to live elsewhere, as Mo Farah does (in the US). It was unclear whether he thought it more unpatriotic if the citizen was black versus white, or naturalised versus natural born – again, requests for further explanation went unanswered.

Mo Farrah’s situation was a useful illustration of how the so-called Muslim ban was not just a lot of hot air on social media. As a naturalised citizen myself, I was particularly disturbed to see that British and Canadian citizens traveling on British passports to the US were also subject to the order if they had been born in one of the seven banned countries. Naturalised citizens have been bestowed the same rights as natural-born citizens, and by applying the ban to people travelling to the US on UK passports, the Trump administration was both violating legal agreements it has reached with other governments (i.e. visa-free travel arrangements) and unnecessarily discriminating against individuals who have already been screened and vetted as part of a successful naturalisation process. This is the route toward treating naturalised citizens as second class citizens.

I am afraid this is the route that America, whipped up by Trump’s rhetorical and practical war on migrants, is travelling down. It is dangerously easy for the rhetoric to shift from ‘Muslims don’t belong’ to ‘immigrants don’t belong’. And, from ‘immigrants are suspect’ to ‘anyone who has ever migrated is suspect’.

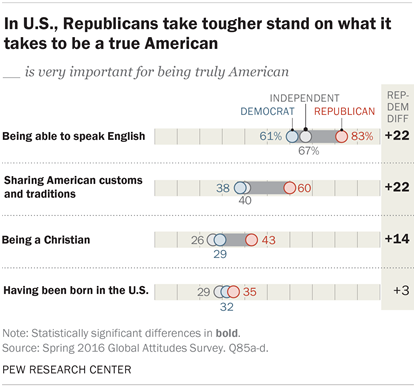

Fortunately, there is still plenty of dissent to the nativist, anti-immigrant viewpoint, as evidenced by the raging arguments going on all over social media. Timely research from Pew Research, published a few days after the Executive Order, explores public opinion across the developed world. They find that relatively few people (32% in both the UK and the US) say that national identity is tied to birthplace. Like most public opinion in the US, views differ based on partisan identity. Republicans are more likely than Democrats and Independents to think that being able to speak English, sharing American customs and traditions, and being a Christian are very important to being truly American. Interestingly enough, there is less partisan difference on the issue as to whether having been born in the US is important.

Since that fateful and stressful weekend, the judicial process kicked into high gear, and after several state lawsuits were filed, a federal judge temporarily stopped the government from enforcing key parts of the ban. The rule of law has held, for now. With any luck, anti-immigrant sentiment can be similarly contained.

© Sousa and Machado http://www.sousamachadoarts.com/