This blog post originally appeared on the Media@LSE Blog on 19 October 2021.

Most of the time, and especially on issues like international conflict that involve high degrees of gatekeeping around sources on the ground, political elites have the most significant power to shape what gets published as ‘news’. But this has changed due to social media: readers and viewers now have more influence over elites’ agendas. For example, audiences can post comments on news articles and directly engage with established figures in media and politics on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. This raises questions about how and in what circumstances these kinds of activities might challenge the usual direction of information cascades. In an increasingly diverse news environment, how do social media and traditional mass media interact—and what does this mean for journalism as a practice?

In our recently published open-access study, we address these questions by analysing over 5,000 Facebook comments responding to how the Tagesschau (Germany’s most significant and most-trusted public broadcaster) covered events surrounding the murder of university student Maria Ladenburger (known as the ‘Maria L.’ case). In October 2016, Maria was raped and murdered on her way home from a medical student party. Then, on 3 December, German police announced they had arrested a refugee in connection with the case. Yet the Tagesschau only covered the ‘Maria L.’ case two days later on 5 December. As a political news broadcaster, the Tagesschau typically doesn’t cover non-politically motivated crime. Yet, as our study shows, this omission prompted backlash among a small group of social media users who accused the Tagesschau of attempting to conceal crimes committed by refugees: to them, the case was obviously political because the perpetrator belonged to the 1 million refugees who German chancellor Angela Merkel had admitted to Germany in 2015.

Examining how this turnaround on whether to cover the case happened within 72 hours matters for two reasons. First, it speaks to cultural anxiety linking asylum-seekers and refugees with crime in receiving countries. While evidence from the US and the UK contests the link between refugee resettlement and violent crime rates, domestic insecurity remains a dominant theme associated with migrants in media coverage. Second, it came at a time when the welcoming atmosphere that had sent Germans to greet Syrian refugees at the Munich train station in 2015 was fading. As we discuss later, there may be a parallel with current events surrounding the resettlement of Afghan refugees in Europe and North America.

Tracking Facebook comments about the ‘Maria L.’ case in Germany: a tumultuous 72 hours

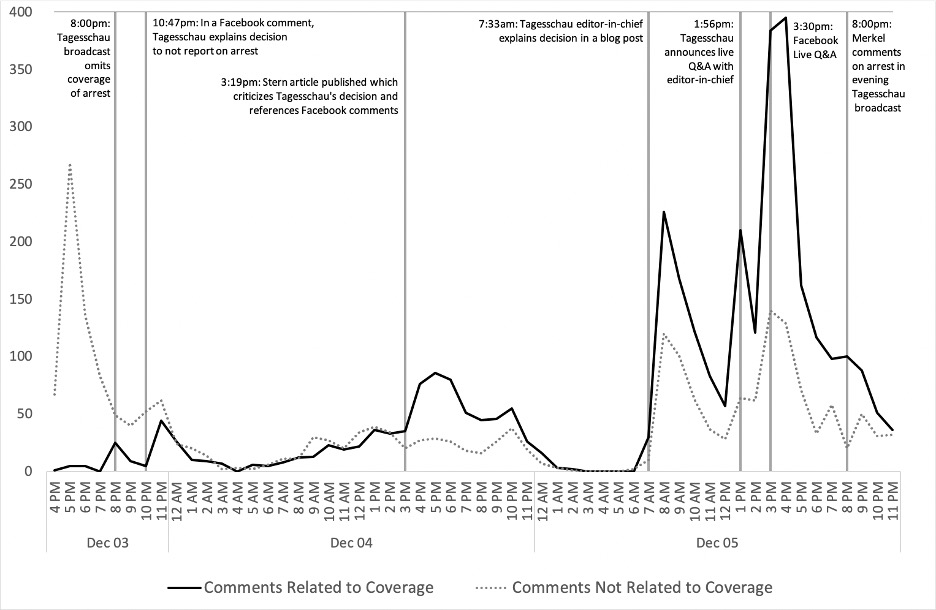

Figure 1 displays the overall dynamics of comments during this three-day period, with particular focus on those related to the Tagesschau’s choice of (non)-coverage (indicated by the solid line).

At first, comments posted to the Tagesschau Facebook page on 3 December—the day police investigators announced that they had arrested a refugee as the prime suspect—were mainly expressing condolences to the family. Other commentors launched a debate on whether Angela Merkel’s refugee-friendly policies were to blame for the murder.

Yet the Tagesschau did not mention the arrest on its prime-time broadcast. A small group of users criticized this perceived omission on Facebook. The Tagesschau responded to this initial criticism with a statement on Facebook explaining that the murder was a region-specific criminal act that did not belong on a national political news programme.

However, this motivated more users to question the Tagesschau’s editorial decision. The next day, on 4 December, left-leaning magazine Stern picked up on the growing online discontent. It published an opinion piece arguing that the Tagesschau’s decision not to cover the case would only worsen the growing public cynicism surrounding legacy media. Our analysis shows this generated even more critical comments explicitly citing the Stern piece, as well as other international newspapers that had also published similar stories.

Finally, with criticism continuing to mount, the Tagesschau issued a longer statement on 5 December, and also held a live Q&A on Facebook that featured the editor-in-chief. Despite acknowledging the growing discontent—and offering to cover the story during its daytime programme—the Tagesschau was unsuccessful at stemming the growing volume of critical comments posted to Facebook. Eventually, that evening, a Tagesschau journalist interviewed Angela Merkel about the developments in the ‘Maria L.’ case.

Audience feedback and migration issues: an uncertain future for public news organisations?

Our analysis demonstrates how social media users—highly motivated ones, most likely—can push back to shape news agendas. In this case, two specific factors were especially important. First, ‘Maria L.’ involved an issue that had both international (i.e., Germany’s humanitarian commitments to refugees) and domestic (i.e., law and order) qualities, which meant users could plausibly invoke either or both as they criticised the Tagesschau. Second, the main target of their criticism was a public broadcaster, for whom political neutrality is both a value and legal mandate.

These factors highlight a threat to public media organizations that are funded by licensing fees. With growing polarization around contentious political issues such as migration, the Tagesschau has to perform a balancing act to fulfill its dual obligations to ‘work towards a non-discriminatory society’ (p.42) and to give all major social and political forces adequate opportunities to express their views. While the Tagesschau certainly aimed to fulfill the former in the case of ‘Maria L.’, its decision not to cover the case contributed to further public debate and media attention around the refugee status of her murderer.

Implications for journalism practice involving migrants and refugees

Two years later, in a similar case (‘Susanna F.’), the Tagesschau took a very different approach. Journalist Ingo Zamperoni opened the evening broadcast:

As terrible as every case is, rape and murders that are not covered by the Tagesschau happen again and again in Germany. We are primarily a political news organization. Yet after long consideration, we are reporting a murder because the circumstances of this crime make the case a political issue. Investigators have found the body of the 14-year old Susanna in Wiesbaden. She was apparently raped. And the main suspect is a refugee from Iraq. And even though the origin of an offender doesn’t make a difference—offenders are individuals, crimes are crimes no matter where the offender came from—this case will likely heat the current debate about refugees and the dealings with declined asylum cases.

Unlike its reluctant handling of ‘Maria L.’, the Tagesschau directly covered the murder while also making an important point: Germans, not just migrants and refugees, also commit crimes.

This observation matters because of the way that reporting on refugees tends to fall into one of two tropes: either victims worthy of protection or threats needing to be contained. Media research during the European ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015 demonstrated how this was the case. Now, drawing parallels with widespread public support for Afghan refugees, it remains possible that another ‘Maria L.’ case might tip public debate towards threat narratives. Our study suggests that it may not be productive to ask whether public news organizations should cover crimes committed by migrants at all—motivated audiences and other media will likely raise them anyway. Rather, by sensitively yet directly addressing the topic, journalists have an opportunity to complicate the binary victim/threat trope surrounding refugees.